THURSDAY JUNE 14, 2018 COMMUNITY NEWS YOU CAN USE

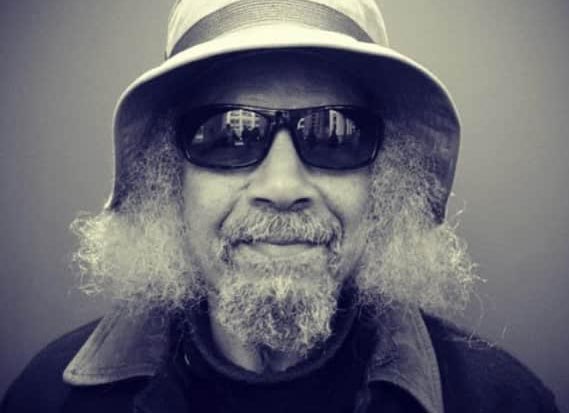

REST IN UHURU,OUR BELOVED ELDER & “THE GRAND FATHER OF RAP”JALAL MANSUR NURIDDINA MEMBER OF THE LEGENDARY LAST POETS HAS JOINED THE ANCESTORS!Message From The Chief Editor:Peace Family,Although one must totally disavow the below writers opinionated Bullshit that,“the group spoke from a standpoint of disillusionment”…..I would never the less strongly recommend that folks in general; And the next waveof young rappers in particular both read the below NY Times obituary and take thetime to discover or rediscover the revolutionary lyrics, videos and still relevant musicmessages of Jalal & The Last Poets during this years 50th Anniversary of the group.CLICK TO THE FOLLOWING SONG & IF YOU DIDN’T KNOW – NOW YOU KNOW!Culture Is A Weapon,Panther-Zulu Nation King, Bro. ShepZulu International Community News Service (ZICNS)____________________________________________________________ _______ OBITUARIESJalal Mansur Nuriddin ‘Grandfather of Rap,’ Is Dead at 73By Giovanni RussonelloJune 13, 2018Jalal Mansur Nuriddin of the Last Poets in London in 1984. He delivered some of the group’s most urgent and incisive verses.Credit

David Corio/Redferns, via Getty ImagesJalal Mansur Nuriddin, who helped establish the foundation for hip-hop as a member of the Last Poets and in his own solo work, died on June 4 at a hospital in Atlanta. He was 73.The cause was lung cancer, said Umar Bin Hassan, a fellow member of the Last Poets.The Last Poets emerged in Harlem at the end of the 1960s, reciting rhythmic verses over conga drumming and speaking directly to the disenfranchised youth of New York City’s black community. The group’s poetry pushed revolution and self-determination, while admonishing listeners about survival in an environment defined by racialized poverty.With his high, declamatory voice and his way of milking words for their sonic potential as well as their meaning, Mr. Nuriddin (pronounced noo-ruh-DEEN) stood out. He delivered some of the group’s most urgent and incisive verses, and although the Last Poets’ lineup rotated over time, he performed with the group well into his later years.By then he had come to be widely known as the “grandfather of rap,” a laurel he proudly accepted.With the release of their debut album, “The Last Poets,” in 1970, the group became an underground sensation, reaching No. 29 on the Billboard album chart and staying on the chart for 30 weeks despite being rarely played on radio. Mr. Nuriddin was fond of saying that the record “sold over a million copies by word of mouth,” though he never had the documentation — or the income — to prove it. As the civil rights movement lost steam and gave way to the separatism of Black Power, the group spoke from a standpoint of disillusionment, although with vigorous attitude. In “On the Subway,” Mr. Nuriddin rapped:Me knowing meBlack proud and determined to be freeCould plainly see my enemy yesYes, yes, I know himI once slaved for him body and soulAnd made him a pile of black goldOff the sweat of my labor he stoleBut his game his game is oldWe’ve broken the mental holdThings must changeThere’s no limit to our rangeMr. Nuriddin may have made his greatest contribution to the future of popular music as a solo artist. In 1973, using the pseudonym Lightnin’ Rod, he released “Hustlers Convention,” an album that unified the black tradition of toasts — rhymed stories about the heroic exploits of renegades and rebels, and the battles between them — with the contemporary sound of streetwise funk.Rapping in a crackling growl, Mr. Nurridin told an extended story of two young men surviving on the New York streets, with lush backbeats provided by Kool and the Gang and A-list session musicians.On “Sport,” the album’s opening track, he wove a boasting first-person narrative about street hustling, cool and deliberate but adamantly paced. Aside from the improvising horn and guitar lines that swept across the album, this represented almost the exact sonic and lyrical blueprint that rappers like Melle Mel and Eazy-E would pick up on a decade later, when they released some of the first major hip-hop singles, using D.J.s instead of live bands.The Last Poets in their early years. From left, Mr. Nuriddin, Abiodun Oyewole and Umar Bin Hassan.CreditMichael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Mr. Nuriddin arrived at the idea to put a funk band behind his verses with the producer Alan Douglas, who had recorded the Last Poets’ first few albums. Mr. Nuriddin said he had meant the album’s contents as a cautionary tale.“I wrote the album so people would sit up, take notice and not become one of the hustlers, card cheats, prostitutes, pimps and hijackers I rapped about,” he said in a 2015 documentary about “Hustlers Convention.”In the documentary, the rapper Chuck D. of Public Enemy called the album a “verbal bible” for understanding the culture of the New York streets.Mr. Nurridin was born Lawrence Padilla on July 24, 1944, in Brooklyn and grew up in a housing project in the Fort Greene neighborhood. Information on survivors was not immediately available.“I had this need to express myself,” Mr. Nuriddin said of his childhood. “Everything was bottled up — not just within myself, but in the African-American people in general. So I began to write poetry.”By his mid-20s, having briefly changed his name to Alafia Pudim, he was becoming known for his facility with words, and for speaking in spontaneous rhyme. (He began going by Jalaluddin Mansur Nuriddin in 1973.) He soon befriended members of the Last Poets, a group with a loose membership that had started in 1968 on Malcolm X’s birthday. He eventually became a core member.Mr. Douglas got wind of the Last Poets and released their first album on his label, Douglas Records. But radio and television avoided the group, partly because of its unflinching attacks on institutional racism, and partly because it often used one particular word.On pieces like Mr. Nuriddin’s feverish “Wake Up Niggers,” the Last Poets spoke directly to the street communities that they sought to help liberate, using an African-American lexicon that had rarely been caught on commercial recordings and alienating many listeners in the process. Record sellers often slapped cautionary stickers onto the “Last Poets” album (“Recommended for Mature Adults Only”) in yet another moment that presaged the conflicted relationship that hip-hop would have with the mainstream.Despite tensions with Abiodun Oyewole, an original member of the Last Poets, Mr. Nuriddin continued performing under the Last Poets name for many years, typically alongside Suliaman El-Hadi. Mr. Nuriddin is featured on Last Poets recordings including the influential “This Is Madness” (1971), the sonically experimental “Chastisement” (1973) and “Scatterap/Home” (1993).

BRO. JALAL MANSUR NURIDDIN: MEMBER OF THE LEGENDARY LAST POETS HAS JOINED THE ANCESTORS!